Written by Amann Mahajan, Editor-in-Chief.

Note from the Editor: I found this story when combing through my Google Drive for an English essay on The Great Gatsby. It struck me as particularly fitting that, once rereading this piece, I found that I’d replicated many of the same ideas in the new essay I’d written; like the Buendías and the Losers’ Club, I found my history repeating itself, like a snake swallowing its own tail. Without further ado, I present to you an essay written during an ebb in the pandemic; a peek back into July 2021 resurfacing in January 2023.

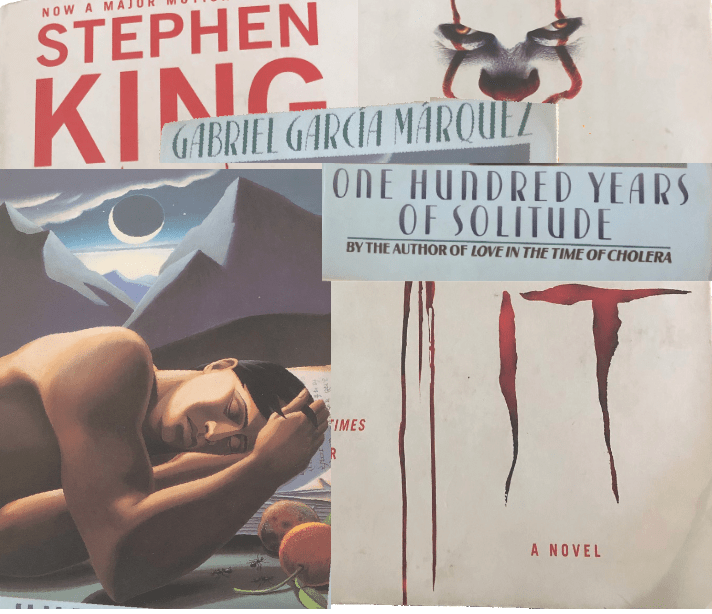

Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude is no doubt a staple in classic literature, utilizing a unique form of storytelling and influencing authors such as Salman Rushdie (most notably in his novel Midnight’s Children). The novel traces the path of the Buendía family, the founders of a small town in the Caribbean dubbed Macondo. Told across generations, it captures Macondo’s development in relation to the rest of the world, as the family shapes (and is shaped by) its surroundings. While the impact of this novel on authors such as the aforementioned Rushdie is quite obvious, small links also connect Márquez’s work to that of another author: Stephen King. More specifically, One Hundred Years of Solitude has strong ties to King’s killer-clown bestseller, It.

It follows seven children fighting the malevolent and “clownish” Pennywise (“It”), a ancient entity preying on children in Derry, Maine roughly every 27 years for sustenance. The children fight this supernatural evil and think they have killed it, only to witness its reawakening 27 years later, when they are adults. At first glance, this sounds nothing like the family saga of One Hundred Years of Solitude, but both stories share core similarities, not only in their settings but in their thematic topics.

The first and most obvious similarity between the novels is in their respective settings. Both Macondo and Derry are towns of moderate size, founded before the twentieth century. Both towns’ histories are convoluted, stained with marks of unsavory events. Both the inhabitants of Macondo and Derry are quiet, ordinary citizens for the most part, going about their daily lives. (In addition, both towns are destroyed at the ends of their respective novels, but we’ll get into that more later.)

However, going beyond more superficial similarities, both novels comment on the cyclic nature of history. In It, as the children confront Pennywise for the second time as adults, they notice that they have to get in touch with their thoughts and emotions as children in order to be able to vanquish the ancient evil. As they draw closer to the final confrontation, they notice that events come full circle; echoes of the past reappear. An apt example: one of the protagonists, Eddie, breaks his arm before confronting Pennywise as a child, and as an adult, the same arm splinters once again as he prepares to reenter Pennywise’s lair. The adults seem to devolve into their childhood selves once more. In fact, one of the chapters is aptly titled “The Circle Closes,” as past and present seemingly coincide. (King’s storytelling itself aids in creating this effect, as the childhood and adulthood confrontations with It occur simultaneously in the novel: the two timelines are set parallel to each other to showcase their similarities.)

Similarly, in One Hundred Years of Solitude, the matriarch of the family, Úrsula, notes the cyclic nature of characters and events in her family. She sees that all the Aurelianos in the family are quiet, withdrawn, and serious, while the José Arcadios are brash and brazen. This moment of the story captures the phenomenon particularly well: “Looking at the sketch that Aureliano Triste drew on the table and that was a direct descendent of the plans with which José Arcadio Buendía [his grandfather] had illustrated his project for solar warfare, Úrsula confirmed her impression that time was going in a circle.” Similarly, she realizes later that conversations are echoed in later generations: “When she said [those words] she realized that she was giving the same reply that Colonel Aureliano Buendía had given in his death cell, and once again she shuddered with the evidence that time was not passing… but that it was turning in a circle.” This idea is reinforced through how those in the family, such as Colonel Aureliano Buendía, have a tendency to make and unmake their work, creating an endless cycle. (“The colonel would “[keep] on making two fishes a day and when he finished twenty-five he would melt them down and start all over again.”)

Thus, both stories comment on the tendency of history to repeat itself. However, while this repetition is beneficial in It, as rediscovering childhood allows the adults to defeat Pennywise once and for all, it serves only to destroy the Buendía family as future generations make the same mistakes as their ancestors. While One Hundred Years of Solitude shows the tendency of humanity to reprise its mistakes and shortcomings, thereby dooming it to destruction, It comments on the power of childhood as the protagonists “remember the simplest thing of all—how it is to be children, secure in belief and thus afraid of the dark.” The novels both discuss the implacable progress of the cycle, but glean a different lesson from the cycle itself.

Similarly, both novels cite the role of willful ignorance in perpetuating evil. In It, the most horrifying scenes of the novel are those in which Pennywise exerts its influence through those in the town, making them kill, and those at the scene simply sit by and watch. In fact, as Beverly (one of the seven protagonists) is in danger of being knifed to death by a crazed bully, a man watching the situation simply ignores the horror unfolding before his eyes. Beverly relates, “He folded his paper, turned, and went quietly into the house.” This, more than anything else, is what is scary about this scene—that there is someone there who can help, but they would prefer to look away.

Again, this is also true for One Hundred Years of Solitude. As the novel progresses, a banana company takes up residence in Macondo, erecting buildings and plantations and hiring hordes of men to work. In one terrifying scene, the laborers demanding better working conditions are rounded up in the square and killed. We see this through the eyes of José Arcadio Segundo, Úrsula’s great-grandson, who awakens after the slaughter in a train filled with the dead from the massacre. He manages to escape the train, finding his way back to Macondo. However, when he arrives and tells a woman about the dead on the train, she says, “There haven’t been any dead here… Since the time of your uncle, the colonel [Aureliano Buendía], nothing has happened in Macondo.” (Similarly, as further generations pass, the colonel himself fades from memory, and everyone is convinced that he is just a fairy story.) The government’s success in making the people of Macondo forget the incident is horrifying, just as the man folding up his newspaper is as scary as the threat of the bully for Beverly.

These themes of memory, of induced forgetting, carry on to the finales of both novels, in which Derry and Macondo are destroyed. In It, after the adults finally vanquish the evil entity, the town of Derry collapses, its infrastructure crumbling. In One Hundred Years of Solitude, as the only lasting Buendía finally deciphers the parchments bearing the history of his entire family, the city is blown away by fierce winds. Both towns are essentially effaced from memory, as if they had never existed. However, while both towns are destroyed, differing feelings accompany each erasure. In It, the obliteration of Derry represents the vanquishing of a timeless evil (since Pennywise fed off of Derry, infusing evil into the town). It is almost a cleansing act. Conversely, the destruction of Macondo is less triumphant and more sad, tired; it marks the demise of a family history that has been fraught with mistakes and solitude.

In the end, the beauty of both novels is their emphasis what it means to be human. Yes, we have a tendency to turn a blind eye to pressing issues; yes, we often make mistakes; yet nevertheless, there is something redeemable in us. In fact, at the climax of the It, protagonist Bill Denbrough realizes that “even at eleven he had observed that things turned out right a ridiculous amount of the time” and that there is an abundance of kindness in the world to believe in. Moreover, though we see the Buendía family err time and time again, we have no choice but to care for them, to see their fundamental weaknesses within ourselves. Both novels are vast and sweeping; they attempt to capture the human experience in the microcosm of a small town. Who knew a book about a killer clown and a book about a big family could have so much in common?