-

Letters to a Young Poet

Reviewed by Christina Ding, a writer.

Photo by Suzy Hazelwood on Pexels.com How exciting it must have been for 19-year-old aspiring poet Franz Xaver Kappus to write to Rainer Maria Rilke—a widely recognized German-language poet and novelist and one of his greatest literary inspirations—and receive a response!

So began a correspondence from 1902 to 1908, encompassed in part by Letters to a Young Poet, the epistolary novel containing Rilke’s advice to Kappus. In it, readers follow Rilke’s travels physically, through explorations of Europe, and intellectually, through his creative process and personal philosophies. Letters to a Young Poet can be compared to a manual for living, replete with thoughtful, poetic language and good-natured guidance.

It’s no secret that we often find ourselves searching for external validation in today’s world. To that end, Rilke stresses again and again in Letters to a Young Poet that people should celebrate struggles, noting that the value of art is derived from within. This is first observed in the opening letter of the book, which comprises a reply to Kappus’ first letter requesting evaluation of his verses. “Nobody can counsel and help you. Nobody,” Rilke responds. Rather, he urges Kappus to ask himself if he “would have to die if it were denied [him] to write.” For Rilke, the worthwhile question is this: “Must I write?” Direct and sincere, Rilke’s words are both relatable and informative. His somewhat counterintuitive attitude applies to not only artists but virtually anyone finding their footing in life. As Rilke and Kappus’ exchange progresses, Rilke further communicates his thoughts on navigating human life and destiny, exploring the inevitability of solitude.

Some of Rilke’s advice may seem unrealistic, and the letters can feel redundant. Yet this only makes the book more authentic: readers understand that Rilke’s own struggles inform his ideals. Reading Rilke’s letters reveals how he himself wanted to approach living a fulfilling life, showing what readers should strive for, even if circumstances deny it.

Rilke’s unwavering sensitivity makes Letters to a Young Poet a meaningful read for anyone, from discouraged artists in existential crises to scrambling teenagers tackling college applications. The book is short, but its content is dense—Rilke’s carefully worded prose urges readers to slow down in the bustle of everyday life. After all, as Kappus aptly notes in the introduction, the letters are important “for many growing and evolving spirits of today and tomorrow.”

-

Cocaine Bear

Reviewed by Carly Liao, a writer.

Photo by Alex Dugquem on Pexels.com If the 2023 comedy horror film Cocaine Bear were a dessert, it would be meringue: a pleasure to sink one’s teeth into, but hardly substantive. Just as eating a meringue leaves one as hungry as before, watching Cocaine Bear gives viewers no greater understanding of its plot or themes than they had going into the theater. Nevertheless, Elizabeth Banks’ most recent directorial endeavor makes for a delightfully enjoyable viewing experience, so long as audiences can turn their minds off and simply indulge in the wonderful ridiculousness of its premise.

The title of the film essentially encapsulates its plot: following a botched cocaine drop-off over the Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forest in 1980s Georgia, a black bear ingests cocaine and subsequently embarks on a violent rampage. Remarkably, the film is based on a true story—though fortunately for unsuspecting hikers (and unfortunately for the poor mammal), the real-life “cocaine bear” died of an overdose shortly after consumption.

The film follows three main protagonists: Sari (Keri Russell), a nurse searching for her missing daughter; Daveed (O’Shea Jackson Jr.), a member of the drug smuggling gang sent to retrieve the lost cocaine; and Eddie (Alden Ehrenreich), the gang leader’s estranged son and a recent widower. Most of the characters remain relatively one-dimensional throughout the film as they navigate the forest and attempt to avoid violent dismemberment. Still, there are a few heartfelt moments in the film, when its characters develop in small yet touching ways: for example, when a minor cop character (Isiah Whitlock Jr.) reveals his affection for a dog that had previously seemed to irritate him, or when Eddie admits that Daveed really has been his friend all along.

Cocaine Bear’s emotional scenes are few and far between, however. Most of the film consists of exaggerated horror-movie fare such as jump scares and gory special effects, which are largely employed for comedic purposes. For instance, in an early scene, a hiker is dragged off-screen by the cocaine-fueled bear; a few shots later, her dismembered leg launches through the air to announce her death. On another occasion, an incompetent park ranger aims her pistol at the rampaging bear, only to miss and shoot through the head of one of her accomplices instead. The dialogue is similarly absurd: in one particularly memorable scene, a young boy discovers a brick of cocaine in the woods and attempts to eat it to show off in front of his crush. The movie’s consistency in its ridiculousness indicates that everything is in good fun, though it may come off as jarring or tasteless to those who find it more difficult to suspend their disbelief.

It would be wise for viewers of Cocaine Bear not to fixate too carefully on such trivial matters as why things are happening or what is going on. The movie does not pretend to be anything other than what it is: nonsensical and darkly comical. Indeed, much of the fun of Cocaine Bear lies in the fact that there is, for the most part, no deeper theme. The film simply asks, “Wouldn’t it be crazy if that happened?” The result is a thoroughly bizarre and entertaining hour-and-a-half affair that is best enjoyed with a large group of friends, copious amounts of popcorn and considerable suspension of disbelief. Ultimately, Cocaine Bear is a solid two-and-a-half-star film: perfect for whiling away a lazy evening with friends, but perhaps not ideal for those who prefer movies with poignant emotional beats or intellectual challenges.

Rated R for bloody violence, gore, drug content, and language.

-

Hold the Girl

Reviewed by Esosa Zuwa, a writer.

“Rina Sawayama 04/30/2018 #47” by Justin Higuchi on flickr.com, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic on flickr.com. See license here. Japanese-British pop singer Rina Sawayama is holding the girl—or holding herself, at least.

Hold the Girl, Sawayama’s second album, was released on September 16, 2022. More personal, toned down, and intimate in its approach than her debut, SAWAYAMA, it still maintains the punchy, alternative, nu-metal, dance-pop sound.

Hold the Girl, mainly recorded in 2020 and 2021, takes listeners on a journey of healing and restoration, bringing to light an inner child long buried inside. The album was birthed out of therapy Sawayama says she took to resolve resonating problems found in her formative years. Thus, Hold the Girl is about not only fixing your problems, but growing up and moving on to who you truly want to be. There is an element of escapism that allows for stillness but then leads you back to the real world, where you feel more secure.

Sonically, the music direction is fairly uniform, with the likes of top producers Clarence Clarity, Paul Epworth, and Stuart Price lending their thematic production to the album. Still, Hold the Girl diverts into distinct subgenres that build on the alternative pop sound. Through the music composition, we witness a range of emotions and experiences, including healing, relief, grief, and anger.

Hold The Girl is specifically structured in a way that represents a process of metamorphosis, as each song change represents a transfer from one state of being to another. The album starts with a short, interlude-like song, “Minor Feelings,” named after the same collection by Korean-American poet Cathy Park Hong, which musically represents long-held, buried-up emotions that compound to become a major hindrance. One lead single, “This Hell,” released in May 2022, is a tongue-in-cheek, feminist pop song referencing Shania Twain, Princess Diana, Whitney Houston, and Britney Spears. It combines country gallop melodies with dance-pop in an in-your-face, irreverent song meant to incense those who take rights away from sexual minorities in the name of religion. The title track, “Hold The Girl,” sets the tone and theme for this album. The song begins with a country-infused R&B ballad before breaking into a hyper-pop chorus, almost in the opposite direction. It starts off sounding powerful and grand, but then falls into an anticlimactic chorus, unable to deliver on its promise. The final chorus, however, is grand and full, as Sawayama pushes herself to achieve what she wants one last time.

Hold the Girl takes a turn in “Catch Me in The Air,” a song similar to a 2000s pop-rock ballad—it’s like the ending scene of a coming-of-age movie. The realization that Sawayama and her mother can support, rather than oppose, one another is belted passionately in lyrics like “Mama, look at me now / I’m flying!” “Frankenstein,” coming after “Catch Me in The Air,” is the loudest, boldest, and most elusive track on the album. It’s a fast-paced, almost frantic pop-rock track infused with techno-indie. It’s monotone but urgent, as Sawayama spurs herself to become a better person, saying she “does not want to be a monster anymore.” “Send My Love To John” mimics “This Hell” in its country melody and message, but differs because it’s from the perspective of an immigrant mother who finally accepts her son’s same-sex partner after years of rejecting him.

Hold The Girl concludes with “To Be Alive,” which wraps things up like a hug to a long-lost loved one who’s finally returned. There is a sense of pure joy at the end of this song, as if one is breaking out of an enclosed shell. Essentially, it is about reconnection and enjoying small moments in life.

Although Sawayama is far from the end of her healing journey, she has reached a point of joy and gratitude. If SAWAYAMA is the brash sibling called into the principal’s office every day, Hold The Girl is the shy, subdued sibling waiting outside the office for them to leave. There is a smooth flow of emotions—which emulates healing—but the album still concludes with a strong message. Hold the Girl ventures into mainstream pop, with a few pockets of Sawayama’s alternative flair inside of them. While remaining true to its theme, it redefines healing through a sonic journey. It’s as if there’s a light coming through this album, leading out into a sunset of hope.

-

The Simpsons: A Case Study in Media Evolution

Written by Kabir Mahajan, a writer.

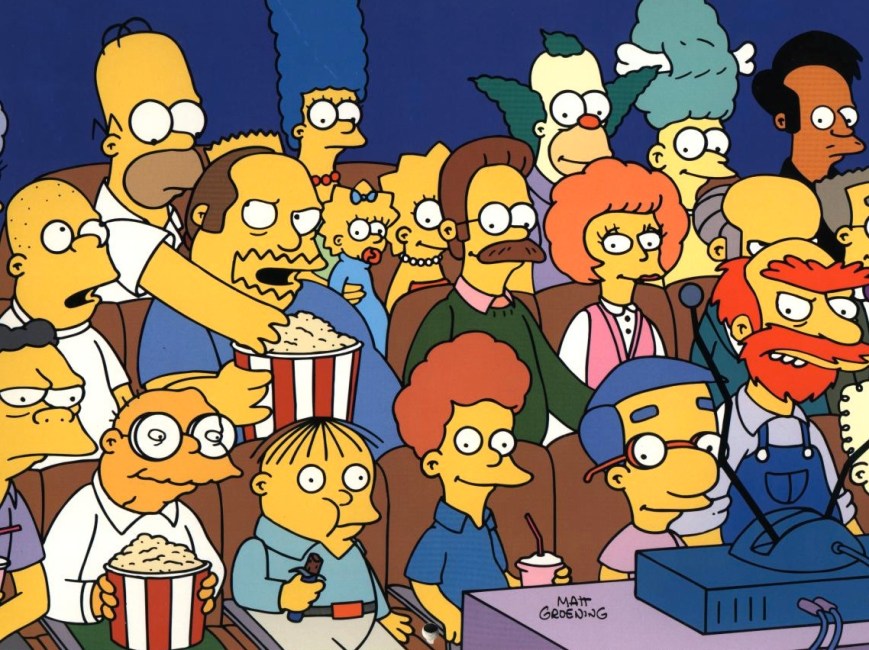

“the simpsons cast on the couch” by SOCIALisBETTER on flickr.com, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic on flickr.com. See license here. Since its debut in 1989, Matt Groening’s The Simpsons has, unequivocally, become a cultural icon. References to it are seemingly everywhere, with the family’s faces plastered on rides in theme parks too and featured in memes spread across the Internet. Over its run, the show has altered its portrayal of a “stereotypical” family, adapted its approach to social issues, and increased its diversity on- and off-screen to better reflect the current world.

The evolution of The Simpsons can best be seen through the changes in its central, “stereotypical” American family. The family consists of Marge, the nagging yet caring mother; Lisa, the intelligent, kind daughter; Bart, the prankster son; Homer, the alcoholic, neglectful father; and Maggie, the cute, silent baby. The portrayal of this family conforms to stereotypes prevalent in the early 90s—Lisa and Marge, the two main female characters, are often portrayed as nagging and self-righteous, Bart is a no-good delinquent, and Homer is the epitome of a bad father, boozy and self-centered. As the series goes on, however, we get more insight and depth into these characters. One episode (“Marge’s Son Poisoning,” 2005) has Bart grow closer to his mother, while another (“From Beer to Paternity,” 2022) shows Homer trying to make up for his parental shortcomings. Gender roles have also shifted through the show as the idea of a “stereotypical” family changes, with Marge taking on more assertive roles outside of the family (she works as a TV show executive and does her fair share of odd jobs). In the 2001 episode “She of Little Faith,” Lisa becomes a Buddhist and challenges traditional religious ideals, demonstrating that non-Western religions and ideas are just as powerful as the dominant religions in Springfield, Judaism and Christianity.

A more significant way the series has changed, however, is in its approach to serious issues: it has gone from satirizing everything to probing pressing issues more gently and reflectively. The Simpsons is known for its unique brand of humor, an attribute that draws millions of viewers in. When watching older episodes, one can expect irreverent humor and relentless jokes about controversial topics, but nowadays, viewers can see a more empathetic, sincere take on major issues. For example, the show’s take on immigration has evolved. One 1996 episode (“Much Apu About Nothing”) shows the town of Springfield cracking down on undocumented immigrants, harassing citizens who they believe are undocumented, and Apu is one of them. The episode still addresses the anti-immigration sentiment, but very irreverently, cracking jokes about immigration and approaching it satire. In a later episode (“Much Apu About Something,” 2016), Apu’s family’s struggles to start a new life in America—we are introduced to his nephew, who goes through the typical second generation identity confusion. Though both take similar political positions, the later episode addresses immigration in a much more sincere, empathetic way.

Over the years, The Simpsons has also worked on representation, adding more characters of color (especially ones that don’t reinforce negative stereotypes), diversifying voice casting, and increasing gender diversity in the production staff. The voice of Dr. Hibbert, the Simpsons’ African American doctor, was originally that of a white actor. In 2021, he was replaced by a Black actor, Kevin Michael Richardson. In 2003, a new recurring character was introduced: Julio, Marge’s gay hairdresser. He was originally voiced by Hank Azaria, but was replaced in 2021 by gay actor Tony Rodriguez. Though these examples show replacements and additions, in one case, a character had to be removed entirely: Apu, the owner of Springfield’s local grocery store, Kwik-E Mart. The character, who has a thick, exaggerated Indian accent, was removed in 2020 after heavy criticism (specifically from comedian Hari Kondabolu, who released a documentary titled The Problem With Apu). The show’s plots also demonstrate a growing social consciousness: more storylines are centered around gender and racial bias. In a 2005 episode entitled “There’s Something About Marrying,” Marge discovers her sister is lesbian, and is forced to face her own internal biases. In these ways, The Simpsons has diversified its viewpoints to offer a multitude of perspectives and to keep itself relevant.

The Simpsons has undergone significant changes over the years as the world around it has changed. The show has adapted its idea of a “stereotypical” American family, challenging traditional gender norms. It has changed the way it handles important issues, using a more empathetic approach, and it has increased diversity, trying to overcome racial stereotypes. The evolution of The Simpsons ultimately serves as a reminder of the importance of media in shaping our cultural landscape and reflecting the values and attitudes of society. It also shows us how the nature of satire has evolved to include more nuanced and thoughtful critiques of social issues instead of brutally poking fun at everything.

-

Men Explain Things to Me

Reviewed by Surya Saraf, a writer.

“Violence doesn’t have a race, class, a religion, or a nationality, but it does have a gender.”

So says historian Rebeca Solnit in her hit collection of essays published in 2014, Men Explain Things to Me. Yet anti-Semitism begets harassment and violence against Jewish people, Black men are shot on their daily errands, and violent crimes occur most in impoverished neighborhoods. Solnit’s text is an important one, no doubt—indeed, it gave rise to the term “mansplaining,” used to describe the condescending manner in which men speak to women—but when reading the essays almost a decade later, it becomes evident that Men Explain Things to Me lacks the increasingly prevalent awareness of intersectionality, or the consideration of overlapping social categorizations. In this case, Solnit fails to consider that women of different classes, religions and races live vastly different lives.

Men Explain Things to Me provides commentary on the oppressed woman: how she is constantly held back in a society that caters to men, and how she must deal with misogynists who talk down to her. Though attempting to be all-encompassing, the essays epitomize what many call the “white feminist” ideology, which is defined as a take on feminism through a purely Western lens. Solnit describes scattered examples of rape and female oppression in Asia and Africa; she calls attention to Jyoti Singh, a woman raped on a bus in New Delhi in 2012, and declares that Singh is to women what “Emmett Till was to African Americans,” as if African American women do not exist or hold enough value to be considered. This is a classic example of “othering,” or classifying a group, often unconsciously, as different. Solnit neglects the fact that African American women suffer on two fronts—as women and as Black women—and simply leaves them out of the mix, an error typifying white feminism.

Ironically, Solnit’s attempts to include all women around the world in her essays only end up alienating them. She starts off the book by blatantly “othering” the Middle East, claiming women there live in societies much worse than “our situations” and that their testimonies have no legal standing in their countries. Solnit’s generalizations reveal the audience her book seems to have been written for: white women. It seems as though these Middle Eastern women are included merely to provide a mask of inclusivity.

So, what is the massive difference between white American feminists and those in the rest of the world, anyway? Western feminist movements are often broken down into First-, Second-, and Third-Wave feminism and characterized by images of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton marching through the streets. Yet, in many developing nations, there is often a heavier focus on women’s struggles with economic disparities and racism because the prevalence of poverty and class difference in developing countries makes feminism a more complex issue. Moreover, activism in non-Western countries is sometimes inconsistent with Western feminist goals (which are often rooted in capitalist, individualistic values), causing many white feminists to view it as misguided and in need of reconstruction. Many women in non-Western countries have claimed to feel pressured or misunderstood by the Western feminist ideology that labels them as eternally oppressed and in need of Western aid.

In her book, Solnit seems to adopt this white savior, white feminist ideology rooted in colonialism. While reading an article from The New York Times on the Taliban, Solnit notes that, in an image, a woman appears to be covered in so much cloth that she is almost invisible—Solnit herself was astonished, mistaking the woman for drapery. She then goes on to label the burqa as a symbol of oppression that masks Afghan women’s true identities, claiming they make women “literally disappear.” Solnit does not seem to grasp the nuances of the situation, as she fails to understand the meaning of the burqa or the hijab: while some women are indeed forced to wear a hijab or burqa, others choose to wear them, perhaps to remain close to God, make a political statement, or seek the modesty it provides. Like many white feminists, Solnit reduces these garments to one-dimensional objects, seeing them as symbols of oppression simply because she does not fully understand their political and social significance.

Despite the book’s faults, it possesses some redeeming qualities. For one, Solnit warns of the dangers of rape culture and the normalization of violence against women. She also does not hesitate to detail female oppression in the West, from rape to catcalling to mansplaining. Additionally, Solnit makes a profound point on same-sex marriage being an indication of the decline in the partiarchy and a loosening of traditional gender roles, leading to a society that may redefine gender expectations altogether. Solnit clearly has an adept grasp of women’s oppression in the West, and certain parts of her book serve as a female voice, or, as she puts it, an inspiration for discourse among all women. Still, the book’s ignorance of intersectionality and of different cultures prevent it from remaining fully relevant in the present day. While Men Explain Things to Me attempts to provide insightful commentary on women’s inequality, it makes generalizations and inaccurate comments about non-Western nations, and, as many white feminist texts do, defines feminist goals and ideologies to be the same all over the world, discounting race, religion and class to achieve its main argument.

-

5SOS5

Reviewed by Aarushi Kumar, a writer.

“5 Seconds of Summer at the B96 Pepsi Summer Bash 2019” by Alex Goykhman on Wikimedia Commons, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license on commons.wikimedia.org. See license here. On September 23, 2022, Australian pop rock band 5 Seconds of Summer (5SOS) released its fifth studio album, 5SOS5. Featuring 19 tracks, the album manages to maintain ties to its predecessors while pushing the band’s lyricism and instrumentation to new heights.

The main themes in 5SOS5 are those of reflection and growth: indeed, the band’s debut showcase for this album was aptly titled “The Feeling of Falling Upwards,” referencing the uncertain, almost free-falling sensation of truly confronting oneself while retaining the hope of impactful personal growth.

Along this theme of reflection, many of the songs in 5SOS5 offer new perspectives on 5SOS’ previous projects. The album that draws the most comparison is their 2015 album, Sounds Good, Feels Good. In fact, many fans joke that “5SOS5 is like Sounds Good, Feels Good if Sounds Good, Feels Good went to therapy.” Both albums cover similar topics, such as youth and personal growth, but 5SOS5 delves into them “on the other side of twenty-four”—that is, it shows a more mature appreciation of the themes, while Sounds Good, Feels Good displays a more youthful, naïve approach to them.

As an example, examine the album’s first non-single, “Easy For You To Say.” This track has incredible lyricism, accompanied by dynamic instrumentation that slowly ebbs and flows throughout the song, finally resolving itself in a crescendo at the end. The lyrics comprise the band members’ thoughts on joining the industry at such a young age and their reflections on personal growth and emotional maturity. With lyrics such as “Last night, I lied, I looked you in the eyes / I’m scared to find a piece of peace of mind / I swear to you each and every time / I’ll try and change my ways,” it is particularly reminiscent of their 2015 song “Catch Fire” and its lyrics of “Now I’m lost in this swirling sea of your sorry eyes / All my life I’ve been waiting for moments to come / When I catch fire and watch over you like the sun / I will fight to fix up and get things right.” Thematically, though, “Easy For You To Say” is a much more mature reflection—the narrator takes responsibility for their previous mistakes, acknowledging the inherent obstacles that are holding them back, while continuing to strive for improvement.

This evolution can also be seen in the instrumentation of the tracks. Throughout the album, the band displays its musical mastery with extensive instrumental breaks that convey incredibly complex emotions without the use of lyrics. While “Catch Fire,” their older release, had loud, thumping, quintessentially pop-punk instrumentals emphasizing the desperation and conflicting emotions being sung about, “Easy For You To Say” has more mellow, balanced instrumentals that create melancholic, nostalgic tone. Moreover, the crescendo at the end of the song shows the band’s true mastery of its instruments—the music conveys the difficulty of personal growth even without lyrical changes. With this crescendo, 5SOS admits that the messy, conflicting desperation seen in “Catch Fire” hasn’t completely disappeared; it’s simply been dispelled in a more constructive way.

These instrumental parallels are seen throughout the album. Songs like “Bloodhound” and “HAZE” are instrumentally reminiscent of their predecessors from the album “Youngblood,” while songs like “Best Friends” and “Emotions” show nostalgia for the band’s first releases. “Best Friends” is a particularly strong reflective song about the band’s eleven-year-long friendship. It’s arguably the song that is the most deeply rooted in their original pop-punk sound: it’s energetic and exhilarating, and it makes you want to get up and dance from the very first chorus. But when you take a second and listen, the song has some of the sweetest lyrics the band has ever written: “Memories I hold to keep safe / And I love to love you, for God’s sake / I got the best friends in this place / And I’m holding on.” The instrumentals with layered chords and harmonies align perfectly to create a nostalgic, exciting, and purely happy song that begs to be performed live.

This album not only shows the growth of the band as a whole, but lets the individual members shine through as well. With “Emotions” and “You Don’t Go To Parties,” we heard the voices of Michael Clifford and Calum Hood (the band’s lead guitarist and bassist, respectively), two voices not heard much in 5SOS’ previous album, CALM. The other two members, lead singer Luke Hemmings and drummer Ashton Irwin, had solo projects and albums with When Facing The Things We Turn Away From in August 2021 and Superbloom in October 2020. The influences of these albums can be seen in songs like “Red Line,” “TEARS!” and “Older” (the last of which is a duet between Hemmings and his fiance, Sierra Deaton).

Because 5SOS5 was the band’s first independently recorded album, the members were able to have complete control over their music. In 2020, the four took a trip to Joshua Tree National Park, and it was there that they wrote their lead singles, “Complete Mess” and “Take My Hand.” As they were in complete separation from the pressures of the industry and their fans, they were able to create what is essentially the purest version of themselves in music. 5SOS5 is entrenched in the themes that the band has sung about since the beginning—yet it also displays the group’s sonic growth through strengthened instrumentation and poetic lyricism. It pays homage to the band’s history while remaking what defines 5 Seconds of Summer.

-

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever

Reviewed by Jasmine Alamparambil, a writer.

“T’Challa Black Panther Movie Poster 2017 NYC 4984” by Brecht Bug on flickr.com, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 license. See license here. Marvel Studios’ long-awaited Black Panther: Wakanda Forever was released on Disney+ on February 1, 2023. Fans of the first Black Panther film, myself included, yearned to see what would become of Wakanda after the death of actor Chadwick Boseman, who played Black Panther King T’Challa in the first movie. The loss of an actor with such a huge role in the cinematic universe was crushing, especially to those concerned about how the timeline would continue. How could there be a Black Panther movie without, well, the Black Panther?

Thankfully, the writers, along with director Ryan Coogler, acknowledged Boseman’s passing by having a similar death befall his character. In the beginning of the film, it is made clear that T’Challa lost a battle with an unspecified illness, similar to how Boseman lost his life to cancer. After his passing, both his sister, Princess Shuri (Letitia Wright), and his mother, Queen Ramonda (Angela Bassett), have to manage their grief and simultaneously lead Wakanda.

In previous films, Wakanda has been established as the most powerful nation in the world due to its natural resource, vibranium (Earth’s most resilient metal, which simultaneously acts as an energy source). However, the main conflict of the movie centers around Talokan, an Atlantis-like nation from Aztec mythology made up of mutants led by Namor (Tenoch Huerta). These people are found to also possess vibranium, posing a major threat to Wakanda—and the entire world. Shuri, filling her brother’s shoes as the sequel’s protagonist, has to find a way to recreate the Black Panther and face the new danger to her people, all while struggling with the pain of loss.

Put simply, this movie is an homage to both Chadwick Boseman, as an actor and friend, and T’Challa, as a brother and son. The grief displayed by the actors and actresses, especially Letitia Wright and Angela Bassett, are in part their real response to the loss of their co-star and longtime friend. That being said, the plot never lingers too long on him, instead focusing on the other characters and how his death affects their and Wakanda’s place in the world. While the film introduces new characters, the emphasis is really on those that the audience is already familiar with. This connects the audience more intimately with the story and the characters’ emotions.

On the surface level, this movie appears to revolve around the basic conflict between Talokan and Wakanda. But the message is much deeper than one of a physical war—it’s actually about grief, and how it permeates every part of one’s life. While the theme of processing grief is used quite often in films, it still shines through in this movie, especially because it stems from real-life events. Having previously introduced characters be the ones grieving is quite the emotional blow, especially to avid fans of the MCU. But witnessing their journey and character development is much more satisfying because of their pre-existing familiarity.

To be fair, the message is a little too direct and often uses the “wiser and more experienced figure” (Queen Ramonda, Nakia or Namor) instead of communicating through more subtle means, like visual cues or detectable emotion from the characters. Much of the dialogue itself is a bit stiff, and the real emotion shines through the acting rather than the writing. That being said, one unique—and favorable—aspect of the film is its unrestrained use of other languages when deemed necessary. Even without subtitles, the tone and body language of the people speaking mirrors what they are saying, so the message still comes across. Having foreign languages weaved effortlessly into the script gives the movie a sense of realism. Especially in a movie about non-English-speaking nations, it’s absolutely expected for everyone to converse in their native language when alone.

There is a lot of time spent on the story itself when it comes to Talokan and Namor, which is interesting enough from a worldbuilding point of view, but rather unnecessary. The plot should have focused more on the already introduced characters and how they cope with the events that have stricken them with grief. I did like the ending, however, which subverts expectations. Without giving too much away, it sends a clear message to viewers, saying that responsibility to others shouldn’t always outweigh one’s own emotions and well-being.

The cinematography serves the subtle but effective purpose of emphasizing the emotions felt by characters. For example, there’s the shaking of the camera when Shuri learns that her brother has passed and her tears begin to fall. It is as if the cameraperson is crying as well, and, by extension, the audience. And, as in the previous film, the scenery is visually stunning. The capital of Wakanda is a perfect mix of village and city, old and modern. The underwater environments of Talokan are a breathtaking compilation of cool colors and organic buildings, and they parallel those of Wakanda. The score, by Academy Award-winning composer Ludwig Göransson, is beautiful, melodic and fitting, and has that rare quality of underlining the plot without overtaking it.

Shuri was already established as a character who immersed herself in her work in Black Panther. Seeing that her brother’s death pushes her deeper into her lab and away from others was expected, but watching her be set apart from her family was not. Because of her leaning toward science over spirituality, her character arc is far different from her brother’s or mother’s. The other characters, especially newly introduced ones, are very interesting, too, although they aren’t sufficiently explored. Riri Williams is definitely my favorite, mostly because of Dominique Thorne’s incredible comedic timing. I also appreciate the expansion of Danai Gurira’s character, Okoye. Before, most of her personality had been her title of the General of the Dora Milaje. In this film, she’s able to grow in her other qualities, like unwavering loyalty, bravery, and just general badassery.

I definitely related to Shuri’s emotions, recognizing in them what I have felt when some of my family members have passed. It’s difficult to find the “right” way to process grief, especially when you feel as if your responsibilities can’t be neglected. It was immensely cathartic to watch Shuri finally learn to take time for herself, growing in the wake of her brother’s death. And yes, I shed many, many tears over the 160 minutes of emotional discovery by characters I’ve grown to love over the four years since Black Panther.

-

King Meets Márquez: It and One Hundred Years of Solitude

Written by Amann Mahajan, Editor-in-Chief.

Note from the Editor: I found this story when combing through my Google Drive for an English essay on The Great Gatsby. It struck me as particularly fitting that, once rereading this piece, I found that I’d replicated many of the same ideas in the new essay I’d written; like the Buendías and the Losers’ Club, I found my history repeating itself, like a snake swallowing its own tail. Without further ado, I present to you an essay written during an ebb in the pandemic; a peek back into July 2021 resurfacing in January 2023.

Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude is no doubt a staple in classic literature, utilizing a unique form of storytelling and influencing authors such as Salman Rushdie (most notably in his novel Midnight’s Children). The novel traces the path of the Buendía family, the founders of a small town in the Caribbean dubbed Macondo. Told across generations, it captures Macondo’s development in relation to the rest of the world, as the family shapes (and is shaped by) its surroundings. While the impact of this novel on authors such as the aforementioned Rushdie is quite obvious, small links also connect Márquez’s work to that of another author: Stephen King. More specifically, One Hundred Years of Solitude has strong ties to King’s killer-clown bestseller, It.

It follows seven children fighting the malevolent and “clownish” Pennywise (“It”), a ancient entity preying on children in Derry, Maine roughly every 27 years for sustenance. The children fight this supernatural evil and think they have killed it, only to witness its reawakening 27 years later, when they are adults. At first glance, this sounds nothing like the family saga of One Hundred Years of Solitude, but both stories share core similarities, not only in their settings but in their thematic topics.

The first and most obvious similarity between the novels is in their respective settings. Both Macondo and Derry are towns of moderate size, founded before the twentieth century. Both towns’ histories are convoluted, stained with marks of unsavory events. Both the inhabitants of Macondo and Derry are quiet, ordinary citizens for the most part, going about their daily lives. (In addition, both towns are destroyed at the ends of their respective novels, but we’ll get into that more later.)

However, going beyond more superficial similarities, both novels comment on the cyclic nature of history. In It, as the children confront Pennywise for the second time as adults, they notice that they have to get in touch with their thoughts and emotions as children in order to be able to vanquish the ancient evil. As they draw closer to the final confrontation, they notice that events come full circle; echoes of the past reappear. An apt example: one of the protagonists, Eddie, breaks his arm before confronting Pennywise as a child, and as an adult, the same arm splinters once again as he prepares to reenter Pennywise’s lair. The adults seem to devolve into their childhood selves once more. In fact, one of the chapters is aptly titled “The Circle Closes,” as past and present seemingly coincide. (King’s storytelling itself aids in creating this effect, as the childhood and adulthood confrontations with It occur simultaneously in the novel: the two timelines are set parallel to each other to showcase their similarities.)

Similarly, in One Hundred Years of Solitude, the matriarch of the family, Úrsula, notes the cyclic nature of characters and events in her family. She sees that all the Aurelianos in the family are quiet, withdrawn, and serious, while the José Arcadios are brash and brazen. This moment of the story captures the phenomenon particularly well: “Looking at the sketch that Aureliano Triste drew on the table and that was a direct descendent of the plans with which José Arcadio Buendía [his grandfather] had illustrated his project for solar warfare, Úrsula confirmed her impression that time was going in a circle.” Similarly, she realizes later that conversations are echoed in later generations: “When she said [those words] she realized that she was giving the same reply that Colonel Aureliano Buendía had given in his death cell, and once again she shuddered with the evidence that time was not passing… but that it was turning in a circle.” This idea is reinforced through how those in the family, such as Colonel Aureliano Buendía, have a tendency to make and unmake their work, creating an endless cycle. (“The colonel would “[keep] on making two fishes a day and when he finished twenty-five he would melt them down and start all over again.”)

Thus, both stories comment on the tendency of history to repeat itself. However, while this repetition is beneficial in It, as rediscovering childhood allows the adults to defeat Pennywise once and for all, it serves only to destroy the Buendía family as future generations make the same mistakes as their ancestors. While One Hundred Years of Solitude shows the tendency of humanity to reprise its mistakes and shortcomings, thereby dooming it to destruction, It comments on the power of childhood as the protagonists “remember the simplest thing of all—how it is to be children, secure in belief and thus afraid of the dark.” The novels both discuss the implacable progress of the cycle, but glean a different lesson from the cycle itself.

Similarly, both novels cite the role of willful ignorance in perpetuating evil. In It, the most horrifying scenes of the novel are those in which Pennywise exerts its influence through those in the town, making them kill, and those at the scene simply sit by and watch. In fact, as Beverly (one of the seven protagonists) is in danger of being knifed to death by a crazed bully, a man watching the situation simply ignores the horror unfolding before his eyes. Beverly relates, “He folded his paper, turned, and went quietly into the house.” This, more than anything else, is what is scary about this scene—that there is someone there who can help, but they would prefer to look away.

Again, this is also true for One Hundred Years of Solitude. As the novel progresses, a banana company takes up residence in Macondo, erecting buildings and plantations and hiring hordes of men to work. In one terrifying scene, the laborers demanding better working conditions are rounded up in the square and killed. We see this through the eyes of José Arcadio Segundo, Úrsula’s great-grandson, who awakens after the slaughter in a train filled with the dead from the massacre. He manages to escape the train, finding his way back to Macondo. However, when he arrives and tells a woman about the dead on the train, she says, “There haven’t been any dead here… Since the time of your uncle, the colonel [Aureliano Buendía], nothing has happened in Macondo.” (Similarly, as further generations pass, the colonel himself fades from memory, and everyone is convinced that he is just a fairy story.) The government’s success in making the people of Macondo forget the incident is horrifying, just as the man folding up his newspaper is as scary as the threat of the bully for Beverly.

These themes of memory, of induced forgetting, carry on to the finales of both novels, in which Derry and Macondo are destroyed. In It, after the adults finally vanquish the evil entity, the town of Derry collapses, its infrastructure crumbling. In One Hundred Years of Solitude, as the only lasting Buendía finally deciphers the parchments bearing the history of his entire family, the city is blown away by fierce winds. Both towns are essentially effaced from memory, as if they had never existed. However, while both towns are destroyed, differing feelings accompany each erasure. In It, the obliteration of Derry represents the vanquishing of a timeless evil (since Pennywise fed off of Derry, infusing evil into the town). It is almost a cleansing act. Conversely, the destruction of Macondo is less triumphant and more sad, tired; it marks the demise of a family history that has been fraught with mistakes and solitude.

In the end, the beauty of both novels is their emphasis what it means to be human. Yes, we have a tendency to turn a blind eye to pressing issues; yes, we often make mistakes; yet nevertheless, there is something redeemable in us. In fact, at the climax of the It, protagonist Bill Denbrough realizes that “even at eleven he had observed that things turned out right a ridiculous amount of the time” and that there is an abundance of kindness in the world to believe in. Moreover, though we see the Buendía family err time and time again, we have no choice but to care for them, to see their fundamental weaknesses within ourselves. Both novels are vast and sweeping; they attempt to capture the human experience in the microcosm of a small town. Who knew a book about a killer clown and a book about a big family could have so much in common?

-

53: New York City Location

Reviewed by Sydney Chan, a writer.

53’s Nama chocolate, served with vanilla ice cream. Photo by Sydney Chan

The king prawn, served on a skewer with lime wedges. Photo by Sydney Chan

The wagyu beef sate, served alongside a creamy peanut sauce. Photo by Sydney Chan

53’s mango pudding, served with greek yogurt ice cream. Photo by Sydney Chan

The Club Razz, a mocktail made with raspberry puree, mint tea, lemon juice, and sparkling water. Photo by Sydney Chan Dumpling skin should be thin and bouncy. Prawns should be filled to the brim with umami flavor. And mango pudding should be so light and fresh that the world around you stops for a moment as you enjoy your first bite. As a Chinese American who’s grown up eating quite a bit of Chinese cuisine, I don’t take my culture’s food lightly. Oftentimes, when a new restaurant says they’re going to put an imaginative twist on Asian food in an upscale setting, they sacrifice either the flavors or the ambience. Fortunately, 53, a new restaurant located on 53 West 53rd Street in Manhattan, checks all the boxes, and then some.

As soon as I walked into this restaurant, I was quickly reminded that New York City is not only known for being the media and entertainment capital of the world—it’s also a foodie’s dream travel destination. The ambience of 53 is incredible, and paired with its amazing food and top-of-the-line hospitality (shoutout to our server Joe!), this spot is top-notch. So grab your fork, or a pair of chopsticks if you’re feeling brave, and dive in.

Before getting into the heart of any restaurant—the food—I want to quickly touch on the interior design and drink menu of 53. The moment you walk in, you’re embraced by warm lighting, wood-paneled walls, and beautifully curved architecture—53 is dedicated to setting the mood and tone of your meal from the get-go. The restaurant also offers private dining in a separate room, but I’m unable to make judgments on that dining experience, as when I went to check it out, the space was not fully finished.

As for drinks, 53 has a vast menu for those both under and over legal drinking age. For obvious reasons, I can’t share any insight into the alcoholic drinks, but the mocktails, known as “Zero Proof Cocktails” on the menu, are creative and refreshing. By our server Joe’s recommendation, I got the Club Razz, a drink made with raspberry puree, mint tea, lemon juice, and sparkling water, and it did not disappoint. It was the perfect fresh and bright palate cleanser between dishes.

The menu structure at 53 is really interesting, once you get the time to take a closer look. Joe kindly told us a bit about each section, but in brief, the dishes are perfect for sharing. The plates found in the “cold/hot” section of the menu were smaller than we expected, but this was truly a blessing in disguise, since we were able to try more things. Most items came in a set of three like at dim sum restaurants. Since we were eager to get a complete feel for the restaurant, we tried a dish in almost every category—steam, grill, wok, and clay pot—which filled us up, but also left us with a few leftovers. Everything was delicious, but I had a few favorites that I’ll introduce in more detail: the xiao long bao, king prawn, mushroom clay pot, wagyu beef sate, and mango pudding.

The first two, the xiao long bao and king prawn, were two of Joe’s favorites, so we had to give them a try. In all honesty, I was a little bit skeptical about the xiao long bao (also known as soup dumplings) at first. Not many places make it right, creating dumplings with a tough skin and/or a dry filling. In particular, I’ve found many chicken dumplings to be on the dry side, so I was a little worried about these ones. However, I was pleasantly surprised. The three little pockets of goodness on the plate held a good amount of soup, and the black truffle took it to another level. With the mellower flavor of the chicken (in comparison to pork or duck), the truffle added an extra layer of umami and flavor to tie the knot on this dish.

The king prawn was another home run in my book. Served on a skewer with a wedge of lime on the side, this dish is any seafood lover’s dream. Honestly, it’s a dish worth trying for even those who are a little pickier in regards to seafood. What I loved about these prawns was that they didn’t have a briny taste, which allowed for the beautiful spice rub they were marinated in to shine through.

Something I find truly inspiring about Asian cooking is its ability to infuse so much flavor into a vegetarian dish. The mushroom clay pot, full of savory juices, took me to flavor town, packing a punch of savory goodness into every bite. Still, the best part of this clay pot, in my opinion, was the crispy rice on the bottom of the pot. Brown but not burnt, the crunchiness of the rice contrasting with the soft mushrooms was a match made in heaven.

The last savory dish of the night was the wagyu beef sate. You know how the saying goes—“Save the best for last.” The tender beef, paired with the creamy but not overly sweet peanut sauce, was the perfect savory end to the dish. At that point, we thought we were done. That is, until Joe brought out the dessert.

Before long, the nama chocolate and mango pudding were set on our table. I’m not a big chocolate fan, so I definitely prefer the mango pudding, but for you chocolate lovers out there, the mousse is incredibly rich, and paired with the vanilla ice cream, it’s a heck of a way to end your meal. For those who like ending on a lighter note, the mango pudding is superb. You can tell they use fresh mangoes, and the greek yogurt ice cream, something I hadn’t tried before, adds a nice, subtly tart note that I didn’t know I needed until I took a bite.

This restaurant is truly one to remember. After researching a little more about its owner—the Altamarea Group—and all the success it’s had nationwide, their dedication and love for food is hard to miss. Delicious dishes, a beautiful dining room, and incredible service—I’m looking forward to coming back the next time I’m in the city. Until next time!

53 hours (Palo Alto location):

Lunch

Tuesday through Thursday: 12:00 p.m. to 2:30 p.m.

Dinner

Sunday through Wednesday: 5:00 p.m. to 10:30 p.m.

Thursday through Saturday: 5:00 p.m. to 11:00 p.m.Located on 53 West 53rd Street, New York, NY.

-

My Year of Rest and Relaxation

Reviewed by Irene Tsen, a writer.

The drugs are endless, and so is the sleep. So Ottessa Moshfegh’s unnamed protagonist in My Year of Rest and Relaxation spends her year in hopes of being reborn when she wakes up.

The novel’s protagonist seems to have it all: she’s a rich, white, young, pretty Columbia graduate working in a hip art gallery. Yet there’s something missing, and she chases it in a year-long hibernation, broken only by movies, coffee runs, and Infermiterol blank-outs. She downs pill after pill—Neuroproxin, Maxiphenphen, Valdignore, Silencior, Seconols, Nembutals, Xanax, lithium—mostly to send her to sleep, sometimes to banish her sadness or loneliness. Though she retains some semblance of normality at the start of her year of rest and relaxation, by the end, she is locked in a cage of her own making—literally and figuratively.

True to Moshfegh’s style, the narrator, as well as other characters in the book, is unlikable. The narrator celebrates her privilege and wealth and hates life. Her interactions with her best friend, Reva, are shallow at best, toxic at worst. “Don’t be a spaz,” she tells Reva when her mother’s cancer spreads to her brain. Trevor, the narrator’s sometimes-boyfriend, uses her to gain back “all the bravado he’d lost in his last affair,” and she respects him while hating him for his manipulation. The narrator’s enabling psychiatrist Dr. Tuttle is more concerned with doling out new drugs than anything else, and doesn’t bat an eye when the narrator lies that she killed her mom. Relationships, providing a touch of dark humor to the story, are an unwanted burden. Concerned only with their own worlds and what others can add to them, the characters’ magnified faults and brutally honest thoughts paint an ugly caricature of self-centeredness.

The pacing is slow and the plot sometimes monotonous: movie, pills, sleep, repeat. Yet the flashbacks and events separating this muddle reveal a harsh look at the reality of depression, as the narrator finds sleep as the ultimate solution that will “save her life.” These observations, presented in sometimes acerbic, sometimes tragic comments by the narrator, are what make the novel worth reading. Moshfegh’s prose is sharp and unapologetic, the force that propels the story forward when the narrator’s existence is stagnant.

Reading My Year of Rest and Relaxation is not a pleasant experience. There is no romantic adventure and only the barest hint at a happily-ever-after. My Year of Rest and Relaxation is centered around a bleak longing to escape real life into a different person. By exploring the socially stigmatized idea of “wasting” time resting, it confronts hustle culture and internalized conceptions of our worth being based on our productivity (in fact, in the narrator’s view, “[s]leep felt productive”). And it does so in a disturbing, gripping way that blurs the line between sleeping and living. It doesn’t just describe the narrator’s depression—it invites us to wallow in it.